Painting the Real Face of Dander Park

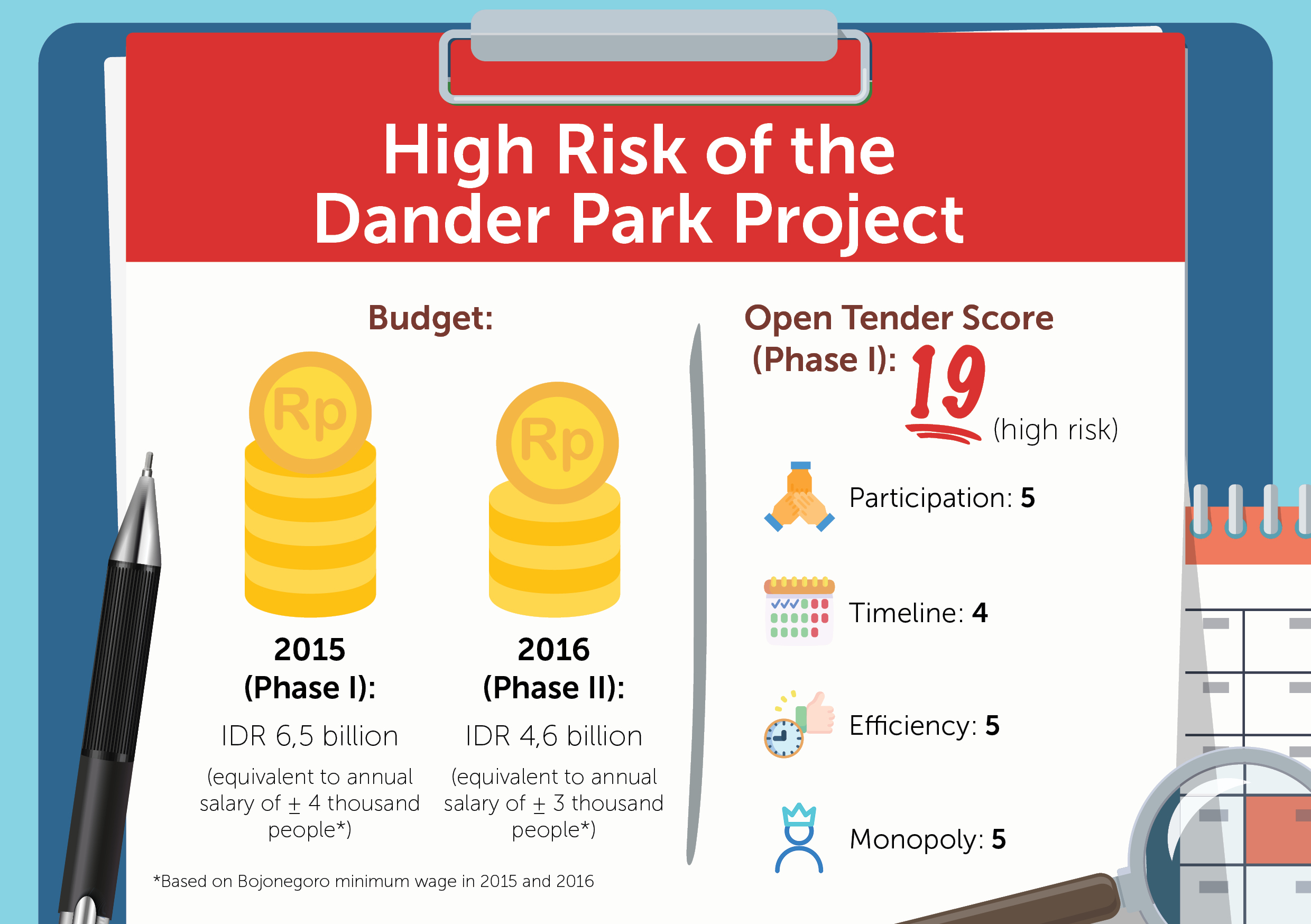

The revitalization of Dander Water Park in Bojonegoro Regency, East Java, last 2015 and 2016 attracted public interest. The project had hefty price tags of IDR 6.5 billion (around USD 485 thousand) for its 2015 construction and IDR 4.6 billion (around USD 342 thousand) in 2016 and was envisioned to be a local revenue generator for the regency. Instead, Dander Park development was rife with questions of possible budget fraud according to the analysis of opentender.net platform developed by the Indonesia Corruption Watch (ICW).

The website gave the project a risk score of 19, which put Dander Park in the at-risk category. The score was the result of the fraud potential analysis method used by the platform to map fraud indications. As many as five variables were assessed in the analysis, namely contract value, tender participation, project efficiency, project implementation timeline, and monopoly.

But there had been signs of trouble even before Open Tender analysis. The modest construction work, for example, that the Commission B of the House of Regional Representatives (DPRD) witnessed during their unannounced visit to Dander Park on January 20, 2016. Ririn Wedia, a journalist from a local media Suara Banyu Urip who had joined the visit and had been closely following the project, also took notice. “There was only the construction for an additional pool and small renovation in some areas,” she said.

Ririn then compared Dander Park with a private-owned water park in the regency. With similar budget value, the latter boasted significantly better quality. Immediately, she suspected skullduggery, especially after three different parliamentary commissions inspected the site in turns.

Aside from Commission B, which was responsible for local taxes and charges, there were Commission C on tourism and Commission D on infrastructure. While Commission B and Commission C were skeptical of the consistency between budget amount and the construction output, Commission D believed the development was completely on track. Ririn’s suspicion grew. Among journalists, WhatsApp groups were abuzz with theories of potential fraud.

However, it was difficult for Ririn, or any other journalist, to confirm or dispel their hunch since Bojonegoro DPRD had not been exactly open about development projects on their tables. An opportunity came when ICW and the National Public Procurement Agency (NPPA) held a training for journalists on public procurement monitoring in Bojonegoro on June 19, 2019. The training gave Ririn and other journalists who participated the lead and data they needed to start investigative work. They also became familiar with the public procurement process and the fraud methods. For Ririn in particular, the experience made her realize the critical role of data in journalism, and that journalists should not rely solely on the information from public officials to underpin their reporting.

Moreover, the training gave the participants the chance to discuss the various public projects in their areas. They made a list of projects at risk of fraud, Ririn said, and Dander Park was included. They also learned how to use the Open Tender platform and, using the new tool in hand, explored every possible irregularity in Bojonegoro’s public projects. The exercise led them to conclude that Dander Water Park development had the highest fraud risk in the regency.

From there, they agreed to carry out an investigation and designed a timeline of three months, divided into three stages. The first month was all about data collection and actor mapping, followed by the legwork to verify their preliminary findings with their sources, including the actors suspected of fraud, in the second month. All pieces of information were then laid out in writing in the third month. Finally, the process ended with story publication by the journalists’ respective media firms.

In general, the investigative work and the stories produced pointed out to a likely under the table involvement of a member of Bojonegoro Local Parliamentin the project’s bidding. A company that had participated in the project’s bid was just one of the several family-run companies owned by the local parliamentarian, and there were other associated companies as bidding participants as well. “The bidding was fixed, and bidding participants were ultimately owned by the same people,” Ririn said, explaining her finding.

During the three months that she spent looking into Dander Park, Ririn received numerous threats. It was an entirely new situation for her to navigate; Ririn had 10 years of journalistic experience under her belt, but Dander Park story was her first investigative piece. She also saw how intimidation had forced some of her colleagues away from this work.

But Ririn was adamant that journalists must unveil the truth, even if it meant compromising their safety. Journalistic work was not just about reporting an event, but also about disclosing information that affected public interests. “And that’s why I was motivated to write about Dander Park,” Ririn added. For her, it was about fulfilling the public’s rights of being informed of the political process in the government and parliament.(*)