Letting Truth Out, Despite Duress

It had never occurred to Ririn Wedia that her life could be akin to a roller coaster ride as it did during the three months prior to November 2019. In that crucial period, Ririn, a journalist of Suara Banyu Urip, was abandoned by her teammates in the middle of their investigation into Dander Park development project. But more than the betrayal, she also received threats from the people who were upset with her reporting. Under the mounting pressure, Ririn’s months of hard work culminated with the eventual publication of her story on November 8, 2019. Moved, Ririn said, “I’ve been a journalist for ten years, and I’ve never written anything like this.” Her eyes glistened with tears.

In Dander Sub-District, Bojonegoro Regency where Ririn is based, a public revitalization project of a water park became the topic of interest of an investigative journalism work – a collaboration of journalists and a local civil society organization. Ririn led the journalists as the team coordinator. Prior to getting the legwork done, she and other journalists attended a training on Public Procurement Monitoring held by the Indonesia Corruption Watch (ICW) and the National Public Procurement Agency (NPPA) on June 19, 2019, at Aston Bojonegoro City Hotel.

Ririn and her team carried out their investigative work from June to October 2019. In the process, they found that some things just did not add up in the project. There were also indications that a member of Bojonegoro House of Regional Representatives (DPRD) might be involved in Dander Park.

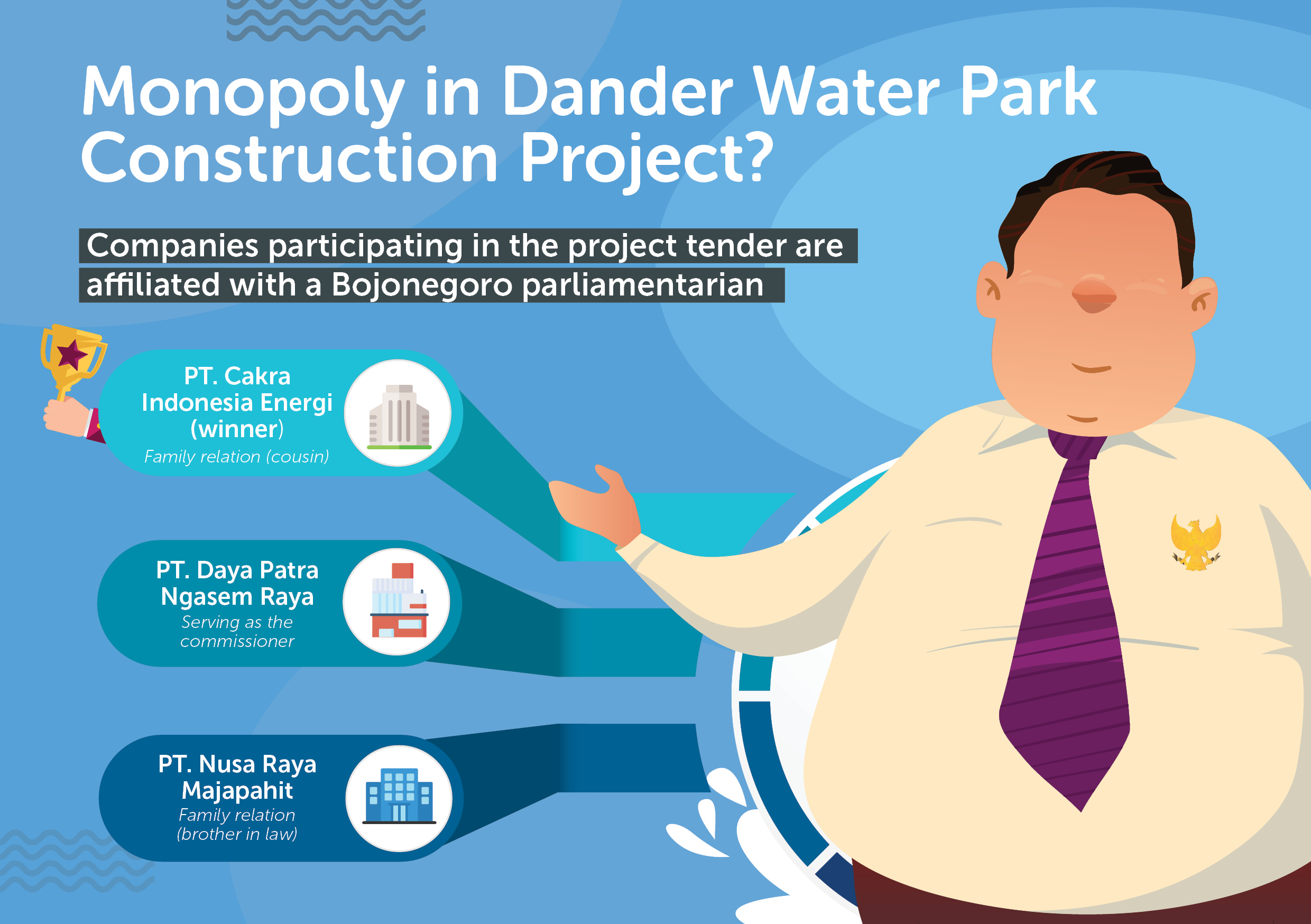

The park was revamped in two phases in 2015 and 2016, each worth IDR 6.5 billion (approximately USD 485 thousand) and IDR 4.6 billion (approximately USD 342 thousand), respectively. In the second phase, three companies participated as construction bidders: PT Cakra Indonesia Energi, PT Daya Patra Ngasem Raya, and PT Nusa Raya Majapahit. Ririn’s investigation revealed that all three companies were affiliated – in one way or another, the people in the company’s top management were related to a member of the Budget Committee in Bojonegoro’s DPRD, a politician of the Democratic Party.

An investigation into the public projects of a local government was never an easy task, let alone valuable projects like Dander Park, Ririn admitted. Her and the other journalists’ safety was on the line. Ririn became even more worried after realizing that the project could involve powerful names – politically and financially. Ririn was also aware that, more often than not, small town journalists did not get the same public attention as their peers in the capital Jakarta.

As if an answer to her concerns, one problem after another piled up during those three months. This included a threat from someone who was perturbed by her investigation. The person in question was the local parliamentarian suspected of his involvement in Dander Park project. He was also Ririn’s source in many of her reporting.

As a journalist, it was common for Ririn to interview legislative members, including the gentleman in this story. However, several days leading to the story’s publication, he reached out to Ririn. Clearly, he was upset. The public official intimidated her, accusing her of plotting and scheming for libel. “Are you investigating Dander Park? Don’t lie now. I’ve heard about it from other people,” she said, repeating the man’s words.

His words threw her off, but she quickly recovered. “I have no idea that it would lead to you,” she said. “I’m a journalist and it is my duty to report this story.”

Unsatisfied with her answer, he asked Ririn to come to his office, saying he wanted to show her some data and a chance to clear the accusations against him. There was only one condition: Ririn must come alone. She refused. She tried to negotiate by inviting him to visit her office instead, Suara Banyu Urip. Now, it was his turn to refuse.

According to Ririn, that was the first time throughout a decade of her journalistic career that she was at odds with a source.

Troubled, she thought of leaving the team at one point, especially since four of her teammates had jumped ship. “I was afraid of what could happen if he read the story, what if the threat escalated? I was terrified,” Ririn said.

But it was one of her closest friends and colleagues that made her feel like the walls were really closing in, and quitting might be her best option. Her colleague, who left during the final stages of reporting, said he was intimidated because of his involvement in the investigation.

The colleague also said he needed to protect his network that he had built and his job. Other than working as a journalist, the colleague was also a social facilitator in one of the government’s programs, Ririn said, and it was his boss in the program that had asked his to leave Ririn’s team.

But he didn’t just leave Ririn behind. He also met with the parliamentarian, apologized, and shared details of the investigation, which was more crushing for Ririn than anything else. “Before the manuscript was published, someone disclosed what we had found,” Ririn recalled bitterly. Ririn confronted her colleague, who then defended his act by saying he was afraid for his life.

It was difficult for Ririn to accept.

Over time, Ririn started to see things in a different light. As a friend, Ririn could understand her friend’s fear of losing a job – especially since what he made as a journalist was barely enough to make ends meet.

Despite all the tribulations, Ririn decided to move forward. She also had support from her very own editor-in-chief, who encouraged her to publish her work immediately. After all, Ririn believed that a journalist has the responsibility to the people to shed light on events and actions that would otherwise stay hidden, including fraud and abuse of power by public officials, no matter how difficult.(*)